New report indicates what may have caused floatplane crash that killed 10 people near Whidbey Island

NTSB investigation indicates what could have caused the deadly floatplane crash

A federal crash team is zeroing in on a mechanical problem that may have caused a floatplane crash that killed 10 people last month near Whidbey Island, Washington.

A federal crash team is zeroing in on a mechanical problem that may have caused a floatplane crash that killed 10 people last month near Whidbey Island, Washington.

According to a report released Oct. 24 by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), investigators are focused on a key part of the plane's pitch control system, which allows the pilot to steer the plane up or down. They found the components of the horizontal stabilizer actuator - a barrel-like mechanism in the tail of the aircraft - had separated.

"Once it separates, the pilot doesn't have the ability to control the horizontal stabilizer," said Mike Slack, an aviation lawyer and expert with Slack Davis Sanger. "That's a real problem. When that was lost, aircraft control was lost – the pilot did not have the ability to control the aircraft in pitch from that point."

Slack said the update seems to explain a lot of the questions that surrounded the crash. However, the NTSB will continue it's investigation beyond this part. The chairwoman, Jennifer Homendy, tells FOX 13 that their team has to determine why the piece malfunctions, but they will also continue their work looking at potential factors to ensure they have a full picture of what happened. This update came out of an abundance of caution – essentially a warning to other pilots that fly similar planes.

According to the report, the actuator separated where its clamp nut threads into the barrel section, but the threads were not stripped, which would have indicated the component was pulled apart by some outside force.

Instead, investigators say the actuator was missing its wire lock ring, a simple thin loop of metal that normally keeps the two parts from unscrewing while in use, and the report suggests there's evidence the ring may have been improperly positioned. "The manufacturer’s assembly drawings for the horizontal stabilizer actuator call for a hole to be drilled into the clamp nut to accept the lock ring tang, after it has been threaded into the barrel during assembly. Postaccident examination of the airplane revealed that five holes had been drilled into the clamp nut threads; three holes were damaged such that they would not allow for the full insertion of the lock ring tang (see figure 7). This suggests that it may be possible for a lock ring to be partially installed, with the tang not fully seated in a hole in the clamp nut. Further, it might be difficult to visually determine if the lock ring is fully engaged in the clamp nut hole (depending on conditions such as lighting, viewing angle, and the presence of dirt or grease)."

Exemplar lock ring.

"It could be anything from it wasn’t put together after some sort of overhaul, it came apart somehow, or it was not fully together," explained NTSB chairwoman Jennifer Homendy.

The operator of the plane, Northwest Seaplanes, told NTSB investigators that the part was overhauled in mid-April, just shy of five months before the crash.

FOX 13 reached out to Northwest Seaplanes by phone, e-mail and social media to ask whether they performed the maintenance themselves, or if a third-party was involved in the overhaul of the horizontal stabilizer in April. At the time of publication, the company has not responded.

A lot of attention has been paid to multiple holes that had been drilled into the actuator – what the NTSB has called a "jackscrew."

"The question is: Why were those holes drilled," said Slack. "They (the NTSB) point out the holes were not large enough for the tang, the little piece that slips through that hole, to be fully inserted."

Homendy told FOX 13 they're still looking into what the manufacturer recommends. Their discovery of this issue will lead to the maker of that part to release an updated guide on maintenance that will go out to the owners of 65 similar planes in operation throughout the U.S.

"We identified a major, major concern," said Homendy. "Because of that, (the FAA) is working with us so they can take action on that immediately."

The actuator and two elevators were both shipped to the NTSB Materials Laboratory on Oct. 18-19 for further examination.

We also learned that 85% of the floatplane wreckage was recovered by the US Navy on Sept. 30.

Five additional bodies were recovered during the operation.

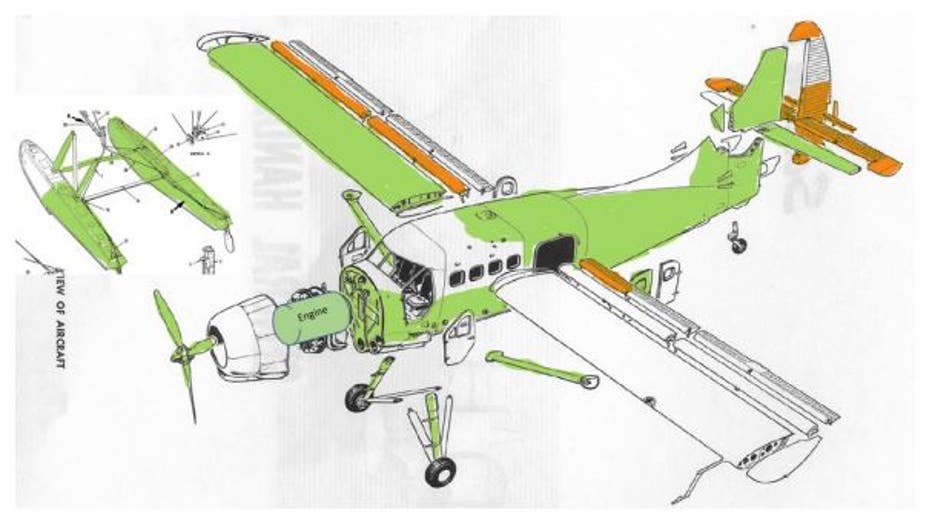

Recovered wreckage highlighted in green. Recovered flight controls highlighted in orange. (NTSB)

The de Havilland DHC-3 Otter was headed from Friday Harbor to the Seattle suburb of Renton on Sept. 4 before plummeting into the water.

Homendy said this plane's original manufacturer, Viking Air Unlimited, is now working on instructions for other operators to review any fleet with a similar de Havilland DHC-3 Otter in operation. The NTSB is aware of 65 such craft throughout the U.S; locally Kenmore Air flies more than a half-dozen of the Otter model float plane. Additional planes are flying in other parts of the world.

That’s important since investigators cannot say what caused the part to fail – which is why this update came out long before the investigation has officially wrapped up.

Earlier this month the FAA issued an Emergency Airworthiness Directive to all DHC-3 Otter operators, warning operators of potential cracks and corrosion in the elevator, the movable surface of the horizontal tail that controls the plane’s pitch.

RELATED: FAA issues warning about type of seaplane that crashed near Whidbey Island

According to the directive, federal officials received "multiple recent reports" of cracks in the elevator. Operators were required to pull the part for an immediate inspection and report their findings back within 10 days.

The sudden failure of the elevator can cause a plane to abruptly go nose-down, similar to witness reports of how last month’s crash in the waters northwest of Seattle looked, said Douglas Wilson, a Seattle-based seaplane pilot and president of aviation consulting firm FBO Partners.

RELATED: New photos show devastation after floatplane crashes with 10 on-board near Whidbey Island

NTSB locates wreckage of floatplane that crashed off Whidbey Island

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) announced that it has located the wreckage of the floatplane that crashed off Whidbey Island last week. All 10 people on board were killed.

Officials previously said determining the probable cause of the crash could take up to two years.

The remains of seven of the 10 people who died have now been identified, officials said earlier this month.