Scientists predict 'dead zone' the size of Massachusetts in Gulf of Mexico

NEW ORLEANS - There's a "dead zone" in the Gulf of Mexico where the water holds too little oxygen to sustain marine life, and scientists are predicting one of the largest in history this summer.

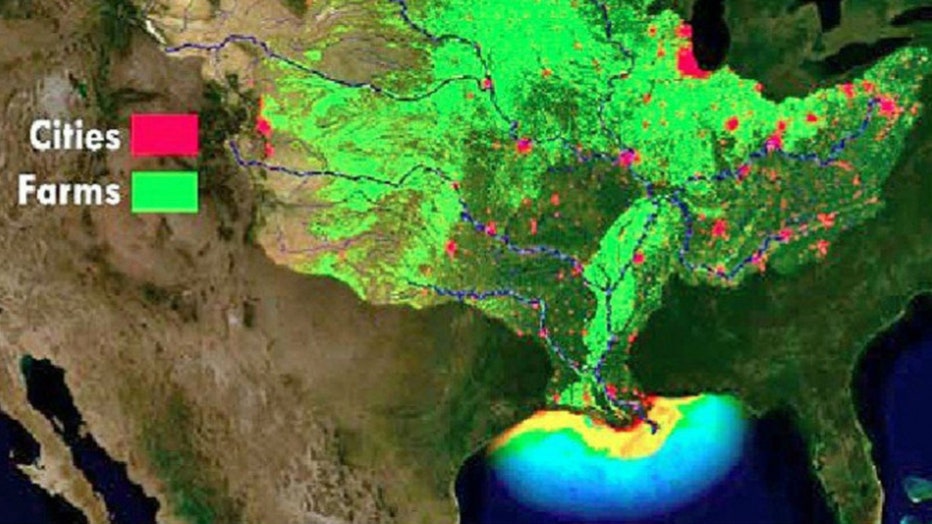

The gulf's dead zone, called the hypoxic zone, is primarily caused by excess nutrient pollution from humans, particularly nitrogen and phosphorous, which run off into the Mississippi River and into the gulf, according to experts. Nitrogen and phosphorous enter the river through runoff of fertilizers, soil erosion, animal wastes and sewage.

"A major factor contributing to the large dead zone this year is the abnormally high amount of spring rainfall in many parts of the Mississippi River watershed," the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said in a news release Monday.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, 31 states and two Canadian provinces drain into the Mississippi River, totaling 41 percent of the contiguous United States and 15 percent of North America.

NOAA scientists are forecasting this year’s Gulf of Mexico “dead zone” – an area of low to no oxygen that can kill fish – to be roughly the size of Massachusetts. (Photo credit: NOAA)

This increased rainfall leads to high river flows carrying large amounts of fertilizer and other nutrients downriver, NOAA said.

The nutrients feed algae, which die and then decompose on the sea floor, using up oxygen from the bottom up in an area along the coasts of Louisiana and Texas.

The low oxygen levels can kill fish and other marine life and also have long-term impacts to living organisms that are unable to leave the area, according to NOAA.

The Gulf of Mexico dead zone occurs every summer and is considered one of the world’s largest.

This year, the low-oxygen area is likely to cover about 7,800 square miles — roughly the size of Massachusetts, NOAA said. A Louisiana-based team has estimated the dead zone will be 8,700 square miles.

It will be measured during an annual July cruise by Nancy Rabalais of the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, who has been measuring the zone since 1985.

The record set in 2017 is 8,776 square miles.

Scientists had said earlier that widespread flooding made a large dead zone likely this year.

A task force of federal, tribal and state agencies from 12 of the 31 states that make up the Mississippi River watershed set a goal nearly two decades ago of reducing the dead zone from an average of about 5,800 square miles to an average of 1,900.

"While this year's zone will be larger than usual because of the flooding, the long-term trend is still not changing," University of Michigan aquatic ecologist Don Scavia, professor emeritus at the School for Environment and Sustainability, said in a news release. "The bottom line is that we will never reach the dead zone reduction target of 1,900 square miles until more serious actions are taken to reduce the loss of Midwest fertilizers into the Mississippi River system."